It has been almost 30 years since Cynthia Volpe, a Bakersfield environmental health code enforcement officer, was murdered, along with her husband and mother, by a landowner whose building she had deemed uninhabitable.

The murder came about a year after landowner and slumlord Robert Lezella Courtney almost beat Volpe to death following a code enforcement action.

A jury was in the midst of deliberating assault charges against Courtney when he snuck into Volpe’s home early one morning and shot the family. He was later pursued by law enforcement officers and was gunned down after putting up a vicious fight.

Courtney got Volpe’s personal information from the Department of Motor Vehicles, and the incident led to a quest for the Cynthia Volpe Act, which would prohibit the release of such information on code officers. This fight is ongoing with California’s DMV.

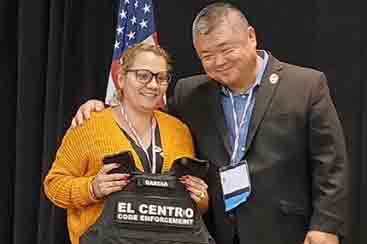

As horrific as this long-ago incident was, there have been many others like it since. Assaults against code enforcement officers, or CEOs, are becoming more commonplace, according to Tim Sun, a Southern California CEO and a safety activist. He contacted Cal-OSHA Reporter to bring light to an issue he says is getting little traction from city officials throughout the state.

The Volpe murder echoes in other states. In West Valley, Utah, Officer Jill Robinson was lured by a property owner she had cited for failing to maintain his yard and having unregistered vehicles on it in 2018. When she arrived, he shot her, then burned her body. Next, he set fire to the home of a neighbor he had suspected of reporting the conditions to the city.

In Pocono Township, Pennsylvania in 2017, a homeowner who was having an issue with mold at his residence went to the township’s municipal building and asked to speak with sewage and building code officer, Michael Tripus, about the problem. He killed Tripus in his office, although Tripus apparently had nothing to do with the issue.

In Long Beach, an officer was shot in the eye. In Colton, a code compliance officer was assaulted by a resident and injured. In Visalia, an officer was attacked with a hammer, but was able to fend off the person with pepper spray until police officers could intervene. These are just some of the many attacks these officers have faced. Many assaults go unreported.

“Threats are happening more and more,” Sun tells Cal-OSHA Reporter. “It starts with random threats, then email threats, then call threats, then to shoving, then to hitting. Then to killing.”

He estimates that only 5% of California cities provide code enforcement officers with protective vests, pepper spray, or emergency communication.

Sun says he has been lucky. His current employer provides him with protection. He will be starting a new job soon that he says he accepted only after learning that the city is dedicated to CEO safety. “I’m trying to fight for the 95% out there who have nothing.”

He feels so strongly about this issue that he has organized an effort through GoFundMe to raise money to provide protective vests in memory of Robinson. The vests cost about $360 each.

A New Age of Threats

Sun thinks municipalities’ reluctance to provide protection comes from the fear of “sending the wrong message” to the community.

He also believes most municipal employers are violating the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which requires employers to provide a safe workplace and proper protective gear. As safety professionals understand, California’s Injury and Illness Prevention Program standard requires employers to assess workplace hazards and take steps to correct them.

In a 2001 survey of members of the California Association of Code Enforcement Officers (CACEO), 63% of respondents said they had been threatened or assaulted. That percentage still holds, Sun opines. “If anything, it’s increased.”

Enforcement personnel of all stripes are routinely seen as the bad guys – who wants to get a ticket? Sun, a former police officer, has worked in code enforcement since the early 2000s. CEOs have traditionally visited sites in a polo shirt, jeans, armed with only a cell phone and a business card.

But things have changed and that’s not good enough anymore in many parts of the state. He sees three types of “big dangers” to CEOs: homeless encampments, illicit drug operations and illegal casinos.

“So you’ve just shut down this guy’s drug business and it’s costing him 50 grand a day,” he says. “Or an illegal internet gambling business 30 to 50 grand a day. And they know your mug. That’s not safe.”

Property owners, the homeless, and illegal proprietors feel they are being picked on and harassed by cities trying to stem the tide of violations. A CEO is the “last straw that broke the camel’s back.”

But agencies are reluctant to provide body armor and other protections, he asserts. “I promise you, it’s not that they can’t afford it. It’s a matter of public perception. They think they are ‘sending the wrong message.’”

Management routinely tells CEOs to “just walk away” from a threatening situation, Sun tells us. They also discourage officers from reporting incidents, he adds, and often blame the officers for inflaming the situation. “That’s what we’re coming up against.”

CACEO is hoping to sponsor a bill in the state legislature that would mandate radios, protective clothing and pepper spray, and possibly TASERs and batons for officers. Sun says he’d also like to see employers required to perform job hazard analyses for the dangers their code officers face. He said the legislative effort is still in its infancy. Sun emphasizes that his comments for this article are his own and not meant to represent CACEO.

“Here’s my goal,” he says. “It’s not to fine agencies across the state, but they need to have a stern warning. What they are doing so far, obviously, is not working.” Sun adds that CEOs are still fighting for full implementation of the Cynthia Volpe Act. “DMV does not automatically protect our information,” he says. “They have actually been fighting us tooth and nail. They claim it would be too costly.”

In a “survival guide” for CEOs, the association recommended the following steps for code enforcement agencies:

- Analyze the workplace and the hazards present due to human elements;

- Create and adopt an officer safety policy that stresses prevention as a primary method;

- Authorize the use of force for self-defense;

- Provide each officer with self-defense tools and proper training;

- Aggressively defend each officer’s safety in the field in the public arena and in city hall; and

- Prosecute attackers to the full extent of the law.

Cal-OSHA Reporter reached out to CACEO as well as the League of California Cities for comment. CACEO responded after our deadline; our online version of this story will reflect the organization’s comments. The league deferred comment to CACEO.